Story by Katy Clune Photographs and Illustrations by Sandra Davidson

“Every day you’ll see the dust, as I drive my baby in my Magic Bus”

“You must do this work with love or you fail. You don’t have to think, but you must love.”

“The potatoes are ready!” calls Emma Slaymaker as the first leaves of fall crunch under her hiking boots. She walks down a gravel road lined with trees and clouded in a damp dusk, announcing, “Potatoes! They’re ready!” Campers call back, teasing and naming her “The Queen of Blue Bus,” while reaching for their chairs and potluck dishes—an annual tradition is ready to be served.

Several hours ago, Ric Jablonski of Roan Mountain, Tennessee, began to slowly heat a pot of pine resin. During a long, aromatic boil—as camp is set up and beers are opened—his hand-picked potatoes are perfectly “baked.” Emma’s announcement means the centerpiece of Saturday night’s communal potluck is finished and dinner begins. At this small festival, many are firm believers in the rewards of patience and taking one’s time.

At 5,400 feet, Mile High Campground is situated in the clouds above Cherokee, North Carolina. On a weekend in early October, only the bright colors of campsites punctuate a misty, drifting fog. For the last eight years, Chris Slaymaker of West Knoxville, Tennessee, has brought his daughter, Emma, and his 1971 VW bus, Lurch, into the mountains off the Blue Ridge Parkway to camp for two nights among like-minded friends. One glance around this end of the campground makes it clear: everyone at the Blue Bus festival drove a VW bus, some from as far as the South Carolina coast.

As the story goes, Chris founded Blue Bus for Emma. Father and daughter have camped in “Lurch” since Emma was born, and their first bus festival together was Buses on the Blue Ridge in 1996, a gathering that ended two years later. In 2007, Chris organized Blue Bus to give Emma the chance, once again, to see her bus friends in the fall. Through the Full Moon Bus Club message board, a hub for VW bus enthusiasts in the southeast, Chris invited his friends and, as they call themselves, fellow “Moonies.” The event stuck. “We’ve had Blue Bus going for eight years,” explains Chris.

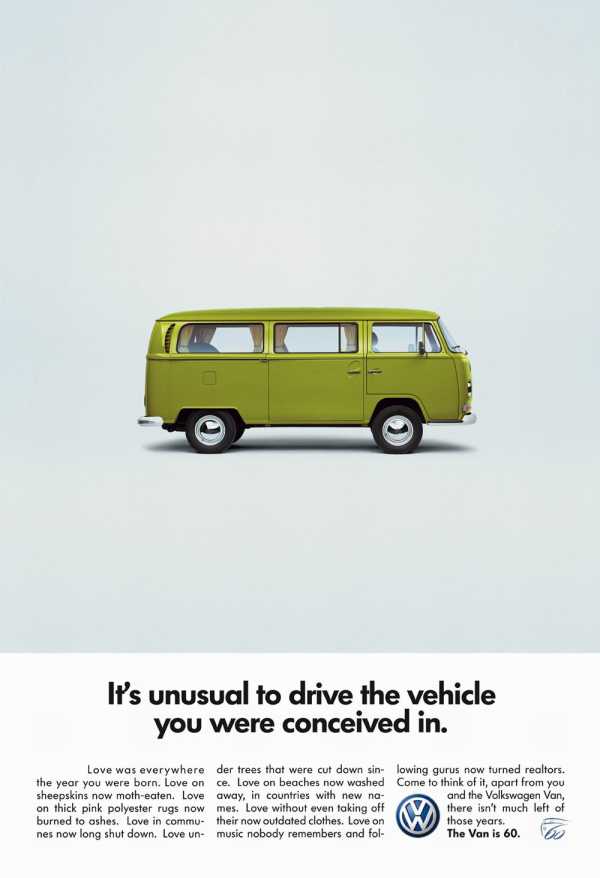

No other car embodies nostalgia like the VW bus. The American vacation was forged on this country’s highways, in its motels, campgrounds and roadside attractions—the bus signifies the joys of each.

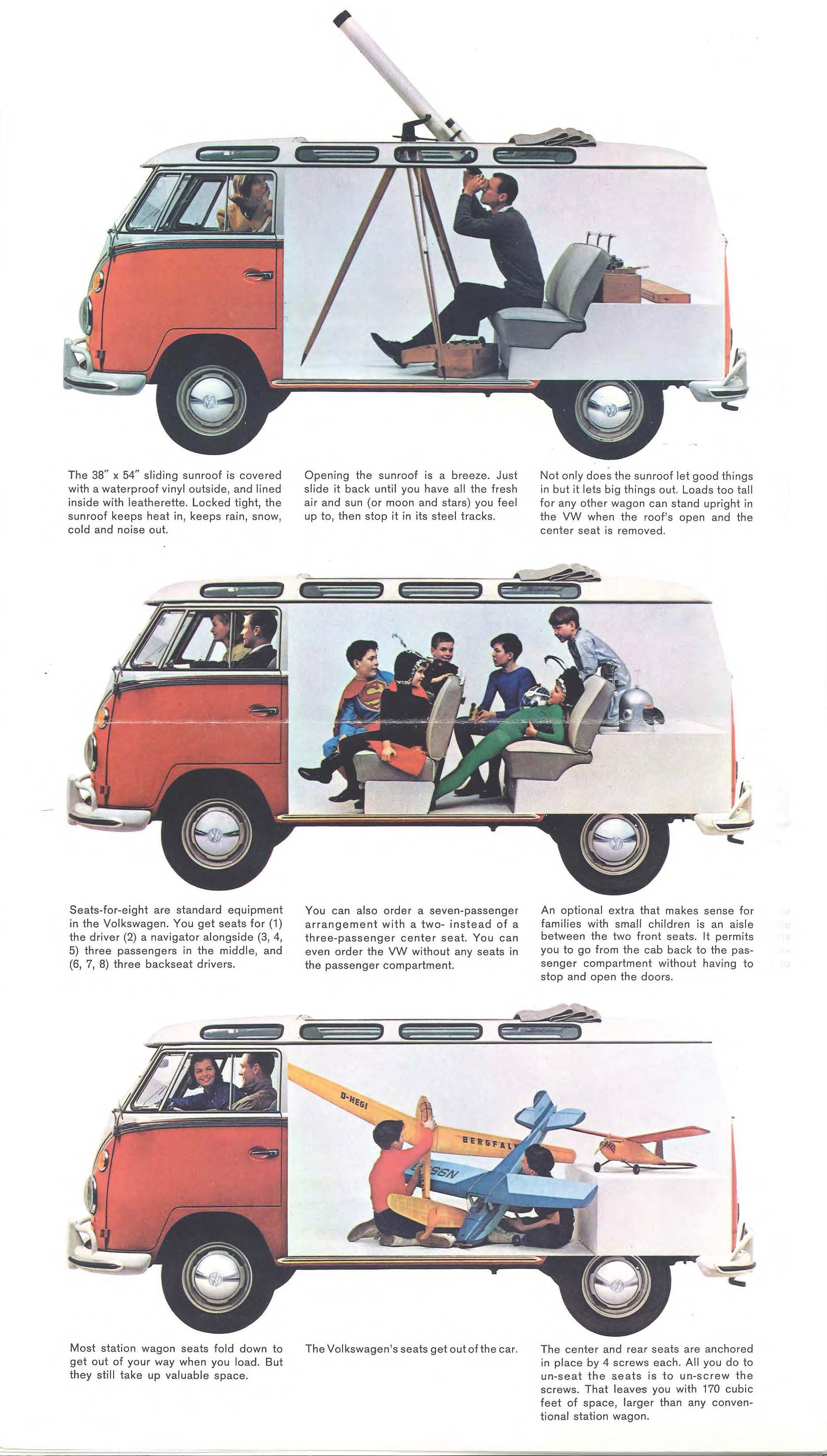

In 1950, Volkswagen produced its first rear-engine bus (Type 2) based on its Beetle sedan (Type 1). Volkswagen entrusted now legendary advertising agency Doyle Dane Bernbach—rumored to be the inspiration for AMC’s Mad Men—to win over American audiences. Their clever ads played into the bus’s ability to serve at home and shine out on the open road, as seen in this historic commercial that beckons bus drivers to explore the great outdoors: “The next time you go for a drive in the country, stay there.” Buses soon epitomized the freedom of the counterculture movement, earning the nickname “hippie van.”

While bus fans can reel off small changes in design and mechanics over the years, one of the greatest changes came in 1967 when Volkswagen stopped production of buses with split windshields and replaced the “Splitties” with “Bays,” single windshield models. In 1979, VW debuted its Vanagon model with optional four-wheel drive and a reinvented, modern face. In 1993, Volkswagen released the Eurovan and relocated the engine to the front. The company kept the classic Type 2 models in production in Brazil through December 2013, but in 2014, the Volkswagen discontinued the iconic buses.

Splittie (1950-1967)

Bay (1967-1979)

Vanagon (1979-1992)

Deemed impractical from almost the very beginning, to love the VW bus is to embrace its fickle nature. The odometers on Splitties and Bay models only count to 99,999 miles, and buses still on the road today surpass this number by hundreds of thousands. Breakdowns are not only common, they’re expected. At Blue Bus this year, Carl Nyberg of Asheville, North Carolina, divulged Volkswagen’s unofficial motto: “Making mechanics out of ordinary people for over 50 years.” This Christmas, Chris took time off work to build a spare engine, and he’ll likely have to make use of it. Traveling on highways with a maximum speed of roughly 50 miles per hour can be stressful, which means in a bus, you’re often taking the scenic route to your destination. This demand to move slow is all part of the appeal, as Director Damon Ristau chronicles in his 2012 film “The Bus.” Admirers are also a part of the lifestyle." Every time we go to a place like this, there are people with cameras,” explains David Prendergast of Greensboro, NC. “When you stop for gas, there are people taking pictures.” A good bus owner won’t mind the attention.

Amidst so much history, origin stories are especially important among the VW bus crowd. Narratives of how you discovered your first bus or festival take two forms: pure serendipity, or simply being born into it. “How do you become a Moonie?” asks Chris. “You just show up.”

Fate is ever-present on a VW bus. When Chris had to retire his first Lurch, a ’68 model, he found a near-identical ’71 replacement in the paper the very same week. Art and Halina Long of Hendersonville, North Carolina, found their ’89 Vanagon by way of Hurricane Katrina. Art saw her for sale online in 2005, missed the chance to buy her, and then, “A year later it popped back up with the same pictures, but only this time it had roof damage. I got her from Slidell, Louisiana, after Hurricane Katrina.” For Carl, he discovered Blue Bus by chance. After finishing a week’s work as a National Park Service Ranger in Waterrock Knob, Carl took his bus to the nearest campground, Mile High, and drove right into the middle of Blue Bus.

For others, buses have always been a part of life. Mitch Davis of Alexander, North Carolina, says, “I’ve always had [VW’s].” He worked as a mechanic at a VW dealership between 1973 and 1987, and his first Volkswagen was a ’57 black Beetle. His bus is a ’65 Splittie, with wood paneling, the original kitchen appliances, plaid curtains, and a hammock that was designed to be hung across the driver and passenger seat as a child’s bed. When a coworker told Mitch he found an old bus, Mitch explains, “I wasn’t even looking for one.” He bought it for $100—a steal—but “the interior was black from mold, and there was a horrendous smell. The hinges were frozen and the canvas was torn.” It took Mitch eight months to lovingly restore the bus, which he painted the original factory shade of forest green with white accents.

David grew up camping in buses and has also been around VW’s for years. When the chance came up to buy a 1984 Vanagon Westfalia Camper of his own, he jumped. Like Chris, he took his daughter on trips from the start. “She knows how to work everything,” he says. “Put the top up, bring it back down, the refrigerator—all the little quirks.” Like others at Blue Bus, he keeps in touch with his VW family via the Full Moon Bus Club website and Facebook group. Bus friends nicknamed his Vanagon, for better or for worse, at one of the annual festivals. “Turd is the unofficial name of the bus,” he says amusedly. “I don't really have a name for it.”

With past incarnations so much a part of any VW bus, customizing your vehicle is a delicate balance between respect for its original form and personal flair. Kathy and Leslie Thompson Folds of St. Helena Island, South Carolina, explain, “If they come with a name you’re not supposed to change it.” They kept the name “Lil Sebastian,” but commissioned artist Ken Mitchell of Salem, Massachusetts to paint their 1986 Vanagon. Using One-Shot sign enamel paint and inspiration from the South Carolina coast, Ken transformed Sebastian into an underwater mural on wheels. Like so many aspects of VW culture, this work takes time: Ken camped in Kathy and Leslie’s drive, and the three became friends over his palette. Other customizations are far less elaborate: Art explained how a fellow Blue Bus camper cleverly “rebranded” her black and yellow bus from its Pittsburgh Steelers theme into her “Bumblebee.”

For Chris and Emma, like every VW bus owner, Lurch represents—and even bears evidence of—countless weekends spent under the stars, around fires, with friends old and new. Stickers from bus clubs and festivals decorate Lurch’s surface—badges from years of father-daughter weekends. Emma teases Chris that he may love his bus even more than her. Chris keeps a scrapbook on Lurch in the bus. Inside there is a family Christmas card portrait with Lurch, arty shots of the bus through the years, even a set of Lurch “self portraits” reflected off shiny eighteen-wheelers. There was also the time when little Emma accidently released the parking brake when she was playing inside the bus, sending Lurch moving slowly down their driveway. Chris yelled out “Lurch!” as his daughter sat bewildered behind the wheel. After all, it is Lurch that enables countless good weekends.

Bus festivals are family reunions of sorts, and Blue Bus, while small, is no different. Ric, a close friend of Chris’, comes most years and sometimes brings his own daughter, Teddy. Emma and Teddy used to call Ric’s bus the “Barbie Penthouse.” In the Lurch scrapbook, there is also a photo of young Emma crawling into Mitch’s first VW bus. Blue Bus may only be the second weekend of October, but campers talked excitedly about two of North Carolina’s biggest summer bus festivals: High Country in Crumpler and Every Bus near Greensboro. Laughs center around repair stories and memories from past events—last year’s gathering, festivals from the 90s, concerts from even earlier.

If you’re ready to dive into bus life, this tight knit community is ready to help. No need to be an expert, either. Samba is online VW classifieds for parts and sales, while AIRS (“Aircooled Interstate Rescue Squad”) is a forum “dedicated to assisting the intrepid VW traveler (all models!) when facing the occasional breakdown—of either yourself or your trusted VW. “You don’t need to be a mechanic,” explains Halina. “That’s what we’re all for! You have so much help.” At Blue Bus in North Carolina’s misty mountains, it is clear there is much more to a VW bus than its four wheels and—almost always working—engine.