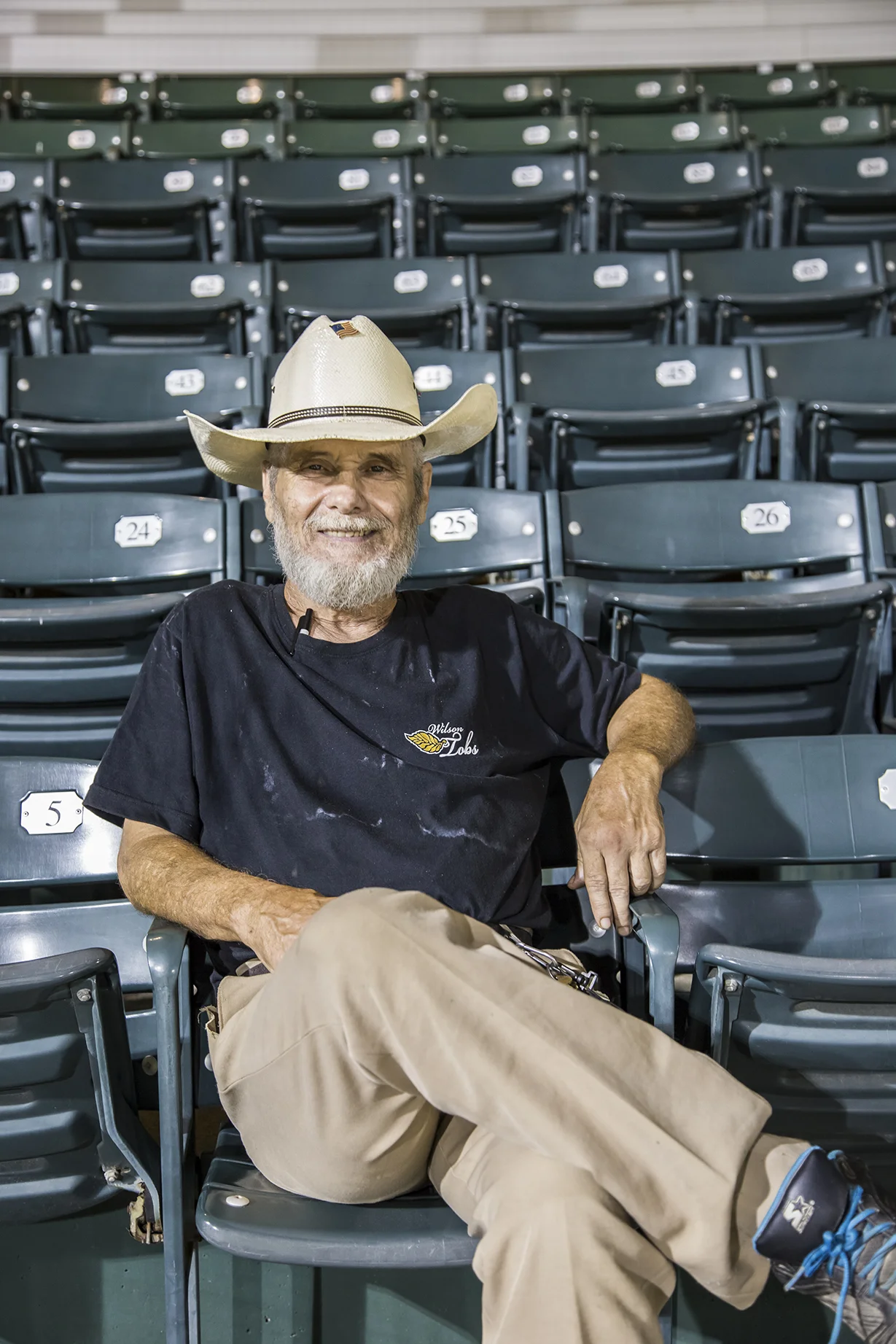

Written by Elijah Gaddis Photographed by Baxter Miller and Annie Cockrill

There isn’t a sport better suited for the long, slow descent into a North Carolina summer night. There’s the high, sharp crack of wood hitting leather. The sustained pause of a ball hit foul, with three endless seconds of anticipation before it hits, thwack, on the top of a wooden roof. And the celebrations: rote applause for catching a routine pop fly mixed with the odd guttural yelp reserved for an adept double play or the elusive home run. These are the sonic accompaniments of a long day--one governed by the oppressive heat and timeclock--slowly wheezing its last few breaths. As the skies slowly darken and the heat mercifully abates, players take the field amid a crowd of people shuffling to their seats, hot dogs in hand and kids set to wander. The game, and the night, wear on and the soft glow of late evening sunlight fades almost imperceptibly toward darkness, until suddenly the dim glare of the setting sun is replaced by the concentrated and unnatural glow of the lights overhead. Night has arrived and with it, baseball.

There is something about the long days and nights of summer that allow people to wring a bit more out of them, to take the few hours in between working days and make them count doubly. And in the mill villages and tobacco towns of North Carolina, those stolen hours were often spent with baseball.

By the late 19th century, people played informal matches, the sort of pick-up games that still populate abandoned lots, front lawns, or fallow fields, all over the state. As a leisure activity, baseball was nearly unprecedented in its universality. But the crowning glory of baseball in North Carolina was the teams and leagues that grew out of a desire to see the most skilled players from every community take on the next town or mill over. Organized baseball of this sort was around by the turn of the 20th century, when a succession of leagues tried to capitalize on a mania for baseball that united communities of working people across the state. Some of these leagues were closer to the semi-professional game we associate with the minor leagues today. Others were comprised of the best workers (and hired ringers) from a particular tobacco factory, cotton mill, or furniture factory. These were players that played not just for a love of the game but for fame, some money, and perhaps, some idea of the abstract promise of baseball.

“There is something about the long days and nights of summer that allow people to wring a bit more out of them, to take the few hours in between working days and make them count doubly. And in the mill villages and tobacco towns of North Carolina, those stolen hours were often spent with baseball.”

Players and fans alike saw in baseball a chance to help transcend the petty indignities and long working days of an industrializing North Carolina. And indeed, it was this newly-arrived industrialization that helped prompt the formation of these leagues and the rise of baseball as a Southern spectator sport. As workers adapted to the demands of single crop agriculture or long factory hours, short bursts of leisure time became more important. And with time now more strictly regulated by the normalized hours of industrialized labor, the potential to squeeze a few hours out of, but not necessarily away from, your employer was essential. To that end, baseball diamonds began popping up all over the place. Most mill villages of any size had employer-built fields and teams, and tobacco towns in the east used some of their increasingly valuable land to erect first fields and then stadiums.

In 1908, the growing city of Wilson fielded the first team nicknamed the Tobs. Short for Tobacconists, it reflected the mutual growth of an industry and a city. Tobacco was growing with the agricultural output of farmers now devoted exclusively to tobacco, the manufacturing labor of a formerly rural group, and the capital of a business class. Uniting them all, in a way, was baseball.

That original Tobs team played for just three seasons before the Eastern Carolina league folded. The team name was revived in the 1920s and again in the 30s and 40s as tobacco became an international business. It was the dominant cultural icon for a city whose downtown was studded with warehouses packed to the brim with bright, golden leaves. The Tobs’ name was not unique in its nod toward the work of many of its players and fans. Greenville briefly fielded a team named the Tobs beginning in 1928, and other manufacturing towns had short-lived teams with almost comically specific names (see: the Thomasville Chairmakers and my hometown Kannapolis Towelers. Go Towelers!) The power of these teams lie in their ability to simultaneously evoke work yet offer relief from it. Though they may have been sponsored by the boss and the company, they were an expression of workers’ culture.

The baseball game was an everyday occasion, an outlet for for the building of community amid the enjoyment of a much loved game. Semi-pro players were both entertainment and possibility. Representative of a life connected to but outside of mill or tobacco work, they were heroes to working people because they came from within their midst. Their presence on the field in neatly-matched uniforms was a high contrast to workaday overalls and aprons. The idea that you could do something like play baseball as a job—whether for love, money, or adoration—must have been nearly unbelievable to working people in North Carolina, many of whom were fighting and losing the battle for fair compensation and working conditions.

Baseball provided a deep and inextricable cultural link between people and the places that they lived and worked. It was not the kind of patrician pleasure seen in the hundreds of essays written about the game during the golden age both of baseball and of literary sports writing. A distant Boston Brave, Brooklyn Dodger, or Detroit Tiger was something you read about in the paper. Baseball was something you played, watched, and felt.

The story from here is a familiar one. Baseball’s fall in popularity accompanied the rise of new diversions found in remote Eastern North Carolina towns and small Piedmont mill villages. Movies and television, cars and shopping malls all competed for the affections and dollars of people increasingly defined as “consumers.” Not incidentally, those changes in leisure were accompanied by changes in work. Gradual mechanization, reorganization, and eventually, outsourcing decimated towns industrial work had helped create. In Wilson, and elsewhere, this left downtown warehouses and factories, empty or torn down and whole neighborhoods nearly abandoned. Many of those empty spaces have yet to be filled.

“There’s never been any one thing that draws a person to baseball. Instead, it’s a game that rewards a kind of solitary commitment amid communal enjoyment. ”

And yet still, there was baseball. The Tobs stopped playing in 1968 and were gone from Wilson for almost 30 years. Despite the long absence, some memory of the team and its importance remained. When a team came to fill the old Fleming Stadium and join the newly reformed Coastal Plain League in 1997, they took the field as the Tobs. Now, the players are all college kids, most with baseball scholarships and a bright future in something, if not necessarily baseball. They come to Wilson, sometimes from several states away, to play baseball and chase individual dreams of glory, money, and recognition. Sitting under the cover of the wooden grandstand, nestled in a residential neighborhood, it’s easy to romanticize this game, this team, and this place. It’s a kind of nostalgia that’s integral to baseball, the one sport whose product is memory, history, and ritual as much as anything else. Surely that nostalgia helps bring the elderly couples, neatly-dressed and attentive, to games. Others come for cheap beer and a hotdog, shared outside with a few dozen other revelers ponied up to the outdoor bar. And children abound, many with gloves in hand, waiting for a foul ball and the possibility of their own small moment of glory. There’s never been any one thing that draws a person to baseball. Instead, it’s a game that rewards a kind of solitary commitment amid communal enjoyment.

“Baseball was something you played, watched, and felt. ”

A mile beyond the ballpark in downtown Wilson, empty buildings still sit awaiting the promise of revitalization and renewed prosperity. The city is well-off compared to many others in the region and state. But it is unalterably changed in many ways. The insignia of the golden leaf, once everywhere in a town ruled by it, now exists mostly on old signs and in faded memories. And, of course, it adorns the uniform, ballcap, and helmet of every Tob as they take the field every year for two brief months. Each season brings more complex memories that mingle with those held from long ago. Last year’s walk-off homer to win a game runs into the distant memories of stemming tobacco leaves, of harvest money in town, of the exploits of players long dead and mostly forgotten. That little tobacco leaf means something more than we give it credit for. Each person can give it his own meaning, one that has as little or as much to do with its history as they please. But taken in the abstract, it’s evoking the complex heritage of North Carolina. A place where work and play commingled, bleeding into one another just as summer days of work in the tobacco fields slowly became summer nights playing at the baseball fields.