As I Knew Him: Senator Robert Morgan

/Introduction by Sandra Davidson Story by Jim Davidson Photos courtesy of the Estate of Robert Morgan

Two weeks ago, my mother called to tell me Robert Morgan had stopped eating. “It’s only a matter of time,” she said.

I knew what this meant.

My father, Jim Davidson, met Robert in 1989. He was a rookie lawyer looking for a break. Robert, also an attorney, was years into a long and productive career in public service. That year, he leased an office to my father. They saw each other there near daily for 25 years.

Many know and remember Robert for his career in public service — he served in the Navy, as a U.S. Senator, as director of North Carolina's State Bureau of Investigation and as North Carolina Attorney General. I know him as a man who means a great deal to my father.

When I graduated from high school, Robert gave me and several friends — including our co-founder Ryan — a behind the scenes tour of the Capitol in Washington, D.C. He guided us through its shimmering halls with the same wide-eyed-wonder and reverence that I imagine he had on his first day on the job as a young Senator in 1975. That unforgettable trip meant as much to my father as it did to me.

As Robert grew older, their bond deepened. My father chopped firewood for him in the winter. He bored out the cores of corn cobs for Robert to feed beloved neighborhood squirrels. In the final months, he designed and printed a scrapbook full of family photos that Robert, incapacitated by late-stage Alzheimer's disease, held in his lap and thumbed through every day.

When Robert died on July 16, our state lost a man who exemplifies what many remember as the greatest generation and my dad lost a father and a dear friend.

This is Robert’s story, through his eyes.

“Hello. I’m Robert Morgan.”

He held out his right hand and smiled, comfortably and confidently — a gesture that marked the beginning of a long friendship.

He died Saturday morning, July 16, 2016, around 10:00 AM, surrounded by his family, friends and caretakers. Since then, there have been numerous obituaries, life summaries and commentaries on Robert Morgan.

Who was this Robert Morgan fellow everyone, from the The News & Observer to The Washington Post to the The New York Times, has been talking about the past week? The answer to that depends on who you talk to, and from what angle they saw him.

That first time I met Robert, my father-in-law provided the introduction. He, like Robert, was a lawyer who was born in a rural farmhouse without running water or electricity. Each had made a name for himself. For the last 25 years, I saw Robert almost every day. We both came to the office early. We both liked a cup of coffee in the morning and to sit and chat as we drank. His office door was always open to me, and mine to him. No topic was off limits, and I never remember an angry word passing between us.

If I were tasked to say in one word what held me most in awe of Robert Morgan, it would be “humility.” For a man to have worn as many hats as he did, Robert never boasted or bragged or acted as if he deserved the best seat at the table. In fact he had a special gift for making the people he met feel they were important.

He liked to eat at the local Waffle House. The people there knew him. They called him, “The Senator,” “Senator Morgan” or “Mr. Morgan.” They saved old bread for him to feed his squirrels. He tipped the cooks. He always ordered scrambled eggs with cheese and hash browns smothered in onions. They knew what he wanted and were often cooking it before he sat down. Sometimes I would go alone, and a waitress would ask apprehensively, “How’s Mr. Morgan?” Misty-eyed, because she knew Robert was losing his faculties.

Even when his memories were spinning away from him, he would still walk up to strangers at the Waffle House, stick out his hand and say, “Hello, I’m Robert Morgan” and launch into an interview asking them who they were, where they came from, what they did, and how their family was. People speak about how he made them feel important, as if they counted for something. For me, his humility, in the light of what he did and the positions he held, is part of what distinguished him.

When I began writing this, on Monday, July 11, 2016, Robert lay on a hospital bed set up in the formal dining room of his home on the Cape Fear River in Buies Creek. The Wednesday before, he had come down with shingles. All they could do was treat the pain with morphine patches. On Thursday, he stopped eating. His life seemed to be slowly ebbing away. Oxygen eased his breathing.

Years ago, when he was coming down with a cold, he said, “I feel puny.” This day, he looked puny. His chest seemed so small. He was surrounded by family and caregivers. He snored quietly and comfortably. Sometimes he stopped snoring, and everyone’s head turned to look on him to make sure he was still breathing.

Over the last five years, he had his struggles. First, it was little bits of memory loss, manifested most particularly with the repetition of the same story. Compounding the memory loss was his struggle with speech. The words would not come. You could see it in his eyes that he was struggling to find the right word. He knew it. He did not shut down, but he was sensitive to embarrassment and said less and less. In visiting him, a nod was enough to know he understood.

Walking became difficult. Toward the end, he submitted to using a walker, then riding in a wheelchair. The last time I know he recognized me was at a party we had at the office on his 90th birthday. He was leaving. Anita, from his team of helpers and Jeannette, his office assistant and right arm for 25 years, were walking him out, one on each of his arms. He looked up at me and said, “You’re Jim!” He seemed pleased with himself for recalling, and I was pleased to have been recognized by him.

When he stopped eating, it was only a matter of time. Margaret told me on the Friday before he died, it was as if he snapped out of the hold his illness and the dementia had on him. Consciousness returned. He could not speak, but he turned his head to the people talking to him. He nodded in recognition of what was said to him. He smiled. He gripped their hands as they spoke with him. The next day he was gone.

As the Secretary of War said when Lincoln passed away, “Now, he belongs to the ages.

Robert spent much of his life in public service.

He was drafted into the United States Navy in 1944, at the age of 19. By the time his train reached California on the way to war in the Pacific, Japan had surrendered. He told me much of his duty after the surrender was ferrying returning sailors from West Coast ports to points east. Then it was back the “ECTC” (East Carolina Teachers College, now East Carolina University) from which he graduated in 1947.

From there, he attended law school at Wake Forest University. In his third year, Dr. Venable Baggett and attorney Dougald McRae drove from Lillington to visit Robert and asked him to run for Clerk of Court. The Clerk was retiring, and they were trying to shape local politics. “Go ahead and run,” he was advised by Dr. I. Beverly Lake, Dean of the law school. “You won’t win, but it’ll get your name out there and might get you some clients.” He ran, but contrary to Dr. Lake’s prediction, he won. During his tenure as Clerk, he was called back into the Navy and served two years, mostly with the USS Valley Forge, an aircraft carrier operating in the Sea of Japan. Upon his return, it was back into politics, but this time on the state level. The rest, as they say, is history.

Robert Morgan and I. Beverly Lake, Sr.

Years Service/Office

1944-1946 United States Navy

1950-1954 Harnett County Clerk of Superior Court

1955-1969 Member North Carolina Senate; President Pro Tempore 1965-1966

1969-1974 North Carolina Attorney General

1975-1981 United States Senate

1985-1992 Director: North Carolina SBI

2000-2003 Founding President: North Carolina Center for Voter Education

Robert’s high political profile led to seats on a number of public boards, including the Board of Regents for the Smithsonian Institution, the Board of Directors for the National Portrait Gallery, the Board of Trustees for East Carolina University, and the Board of Trustees for Shaw University. When asked to serve, Robert stepped up and served.

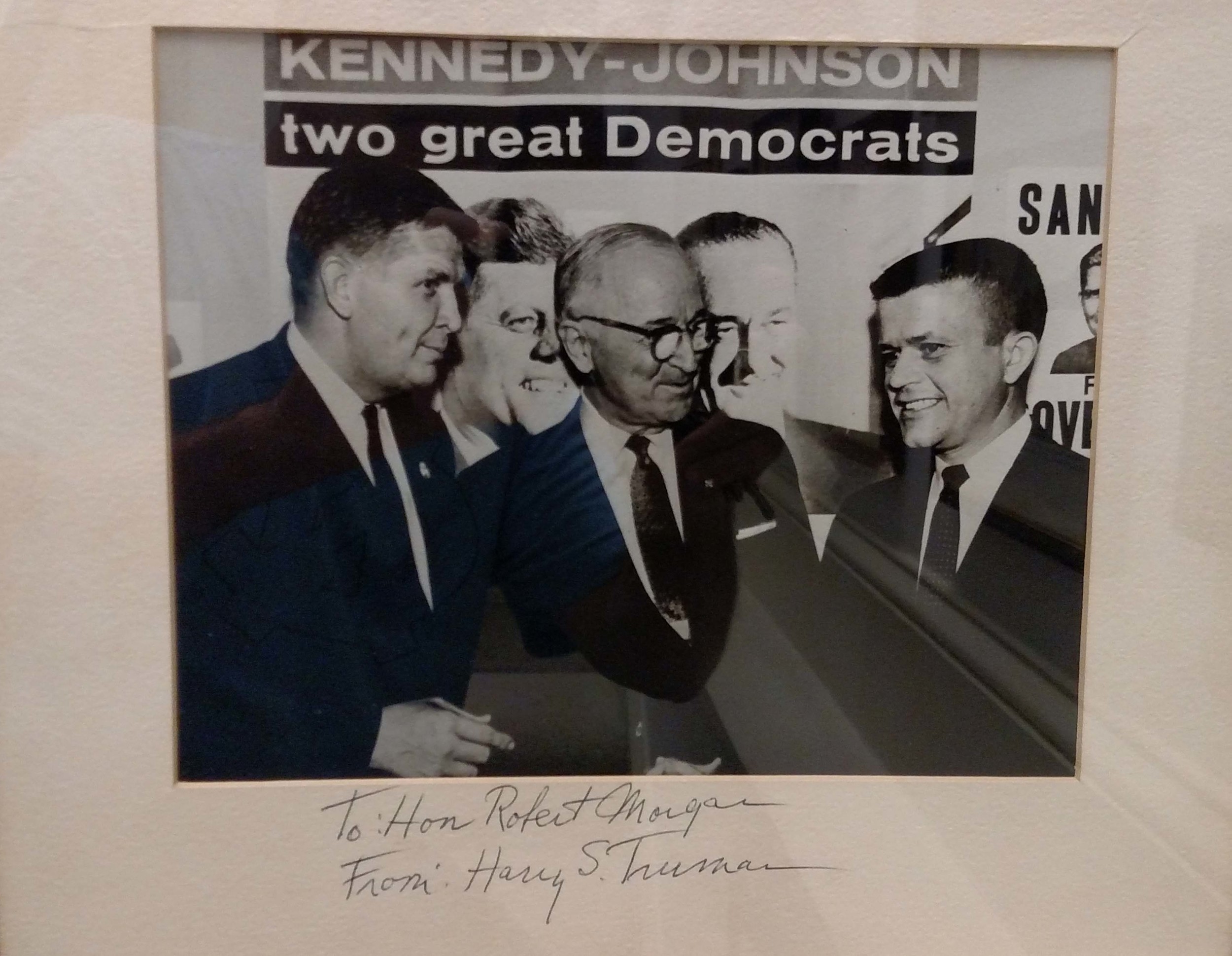

The theory Six Degrees of Separation is based on the notion that, for the most part, we are connected to all living people by no more than six connections. Robert Morgan connects us to every major leader of the 20th and 21st Centuries. He shook hands with Harry S. Truman, who was Franklin Roosevelt’s Vice-President, who knew Churchill, who knew Ghandi. He shook hands with Lyndon Baines Johnson, who was John F. Kennedy’s Vice-President.

North Carolina Governor Terry Sanford, President Harry Truman and Robert Morgan

Robert Morgan serving as North Carolina's Attorney General shaking hands with President Lyndon B. Johnson

Robert Morgan with President Gerald Ford and others

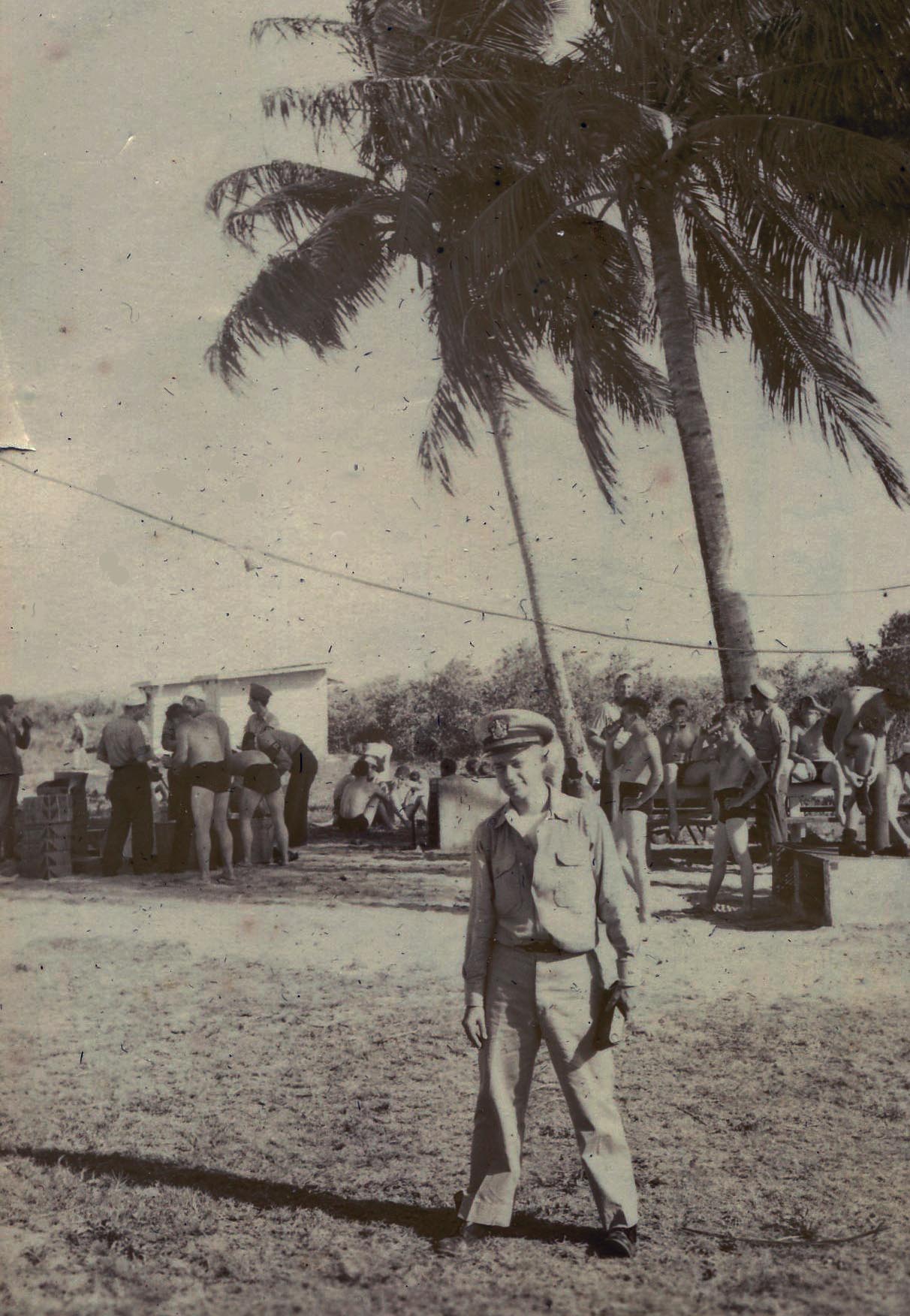

Robert was most proud of his time in the Navy. His affiliation with the Navy began in the naval shipyards in Norfolk, Virginia, after he graduated from high school. He laughed about it when he told me, but he lied about his age to get a job. Drafted in 1944, he spent a time studying physics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and officer training at Northwestern University U. S. Naval Reserve Midshipman’s School in Chicago.

The lives of American pilots were in the hands of Robert operating the radio room of the Valley Forge. “My job,” he said, “Was to guide them out to their missions, to their targets, and see that they made it back to the ship safely.” Here, the sense of responsibility was cast in a forge: lives were in his hands. He never failed them.

In the last few years of his life, he made appearances at Veteran’s Day celebrations wearing his Dress Blues, always proud that they still fit him. Robert was buried in his uniform, and symbols from the U.S. Navy adorned his casket.

Robert's midshipmen portrait

Robert morgan and a friend, circa 1948

Lt. Robert Morgan

Robert Morgan circa 1946

Robert Morgan (on the beach) circa 1946

Robert Morgan in his navy uniform in June 2010

I met Robert in 1989. A young attorney, I needed a place to set up shop. On a hot day late in the summer, Robert Morgan had come to his office at 101 East Front Street near the Harnett County Courthouse in Lillington. At the time, he was the Director of the North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation. His office building was vacant.

My father-in-law, Bill Johnson, also a lawyer and contemporary of Robert’s, practiced one block away. They had locked horns in the 1970's, when Robert was in the North Carolina Legislature fighting to gain university status for East Carolina College and to establish a Medical School. Bill was on the Board of Governors for the Consolidated University of North Carolina system, of which ECC was a part. He fought Robert every step of the way, but lost.

This presented my first lesson from Robert: you can fight like the devil with your rival, and at the end of the day still be friends.

We didn’t spend more than 30 minutes together that day. I guess I passed muster. He offered me the building, we agreed on a number, and he gave me a key. No lease. Just another handshake.

The law office at 101 E. Front Street, Lillington

“By the way,” he said, with a twinkle in his eye, as we were leaving, “If anyone ever calls the office looking for me, and asks for ‘Bob’ Morgan, they don’t know me. My friends and the people who know me call me ‘Robert.’” He was grinning when he said it. I was always ‘Jim’ to him, and he was always ‘Robert’ to me. And, yes... I took a number of phone calls from people asking to speak to “Bob” Morgan.

In 27 years, a handshake was all we needed. He raised the rent $50 one time so we could pay his niece to clean the office twice a month. That was it. When he left the SBI and set up practice with his daughters and their spouses, the building became a satellite location to his Raleigh office, where he worked most regularly.

Gradually, he spent more and more time in the Lillington office, and it came to be the place you would go if you wanted to meet with Robert.

He persuaded me to join Rotary, and we often walked together from the office those Thursday nights. We would talk about our cases, our families, what was happening locally, in the state and the nation. He liked to be driven, so I often found myself driving his car from one place to another. And he would talk, and I would listen.

Robert in his Raleigh office

TELL ME WHY YOU LIKE ROOSEVELT!

'Cause in the year of nineteen and thirty-two

We had no idea just what we would do

All our finances had flowed away

Till my dad got a job with the WPA.

And that's why I like Roosevelt (poor man's friend)

That's why I like Roosevelt (poor man's friend)

That's why I like Roosevelt (poor man's friend)

Good God almighty that's the poor man's friend

Good God almighty that's the poor man's friend.

– "Tell Me Why You Like Roosevelt"

Jesse Winchester

Robert Morgan was “the poor man’s friend”.

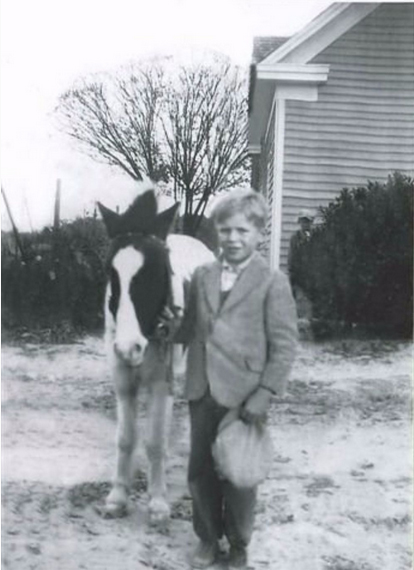

The Great Depression had a huge impact on him. Robert once said, “I remember we used to go to Raleigh, and there would be people with their hands out, with their hats out, begging for money. Daddy would always give them a dime.”

“Mama would fuss at him. ‘Stop it, Harvey. He probably already has more money than you!’ ‘Well,’ Daddy would tell her, ‘He’s got 10 cents more now.’’”

Robert knew what it was to be poor. He saw it all around him and in his home. He also saw that sometimes it just took a little gumption to stand up to the bullies and the bankers.

“Daddy got behind on his crop loans,” he told me once. “The bank said they were going to foreclose, take our farm. Daddy went into the bank and told them, ‘No sir, you’re not going to take my farm. I know you’ve been taking crops instead of money from other farmers, and that’s what you’re going to do with me.’ And that’s what they did. Daddy got his loans right, and he kept the farm.”

About a year-and-a-half ago, Robert stopped coming into the office on a regular basis. He was no longer driving. Jeannette, his office assistant, was picking him up and taking him home then. In the three or four years before that though, there was a lady, homeless I suspect, who would come to visit Robert at the office several times a month. He always gave her $5. Sometimes he gave her a ride across the river to some place she wanted to go.

“When I was growing up,” he reported to an interview for the East Carolina University alumni magazine, “We only had two books in this house: The Bible and Pilgrim’s Progress. Mama read to us every night.”

“We went to Neill’s Creek Baptist Church,” he told me. “Before we got a car, daddy would hitch up the mules and we’d ride in the wagon.” There he learned the lessons of The Beatitudes, The Good Samaritan, and of Christ’s love of the poor. At his funeral, the Reverend Ed Beddingfield, who had worked for Robert in the Attorney General’s office and later became his pastor discussed how Robert had lived the Beatitudes.

Alice Butts Morgan, Robert's Mother

James Harvey Morgan, Robert's Father

Robert as a young boy

Morgan homeplace in Harnett County

He relayed a story told to him by Robert’s son, Rupert Tart. “It was about 1971. There had been death threats against Daddy Robert by the KKK, so we were a little scared. We were in the Food Lion grocery store. We noticed a woman kept looking our way and pointing. We were nervous when she came over to us.”

“She said, ’You probably don’t remember me, Mr. Morgan, but when my mother died, we couldn’t afford a lawyer to administer her estate, and you did it for free. I don’t know if I ever thanked you properly for that. But I did come to see you when I finished high school. I told you I wanted to go to college, that I had been accepted, but I could not afford it. I was only hoping you might have some ideas about how I might raise the money. You paid my books and tuition. I am in a doctoral program now, and should finish this year.’”

“Then she handed Daddy Robert an envelope and told him, ‘I know this isn’t everything you paid for me, but it’s yours and I want you to have it.’” Despite Robert’s protests, she insisted he keep it. When she left, he had tears in his eyes and he told me, ‘I still don’t remember who she is.’”

That was Robert Morgan.

In politics, it was widely recognized that he was above the dirt and nastiness of ordinary politics. He loved to laugh, to hear and tell funny stories. This picture of him on Air Force One was one of his favorites.

“That’s me,” he would tell you, “Sitting in Jimmy Carter’s seat on Air Force One. President Carter had been walking around the plane talking to reporters and all. And when he came back, there I was sitting in his seat! I offered to get up, but he insisted I stay, and he sat on the floor. Imagine that... the President of the United States.”

Robert Morgan with President Jimmy Carter and company on Air FOrce One

Jimmy Carter exiting Air Force One with Robert Morgan

In 1980, Robert lost his Senate seat to John East, a political science professor from East Carolina University, who had the backing of Jesse Helms and his “Congressional Club” fundraising organization. During the campaign Robert became aware his body was not behaving properly. He was diagnosed with an acoustic neuroma. It was operable, but during surgery nerves were damaged. He spent the rest of his life deaf in his left ear and with paralysis on the left side of his face. My wife’s brother went to visit him in the hospital as he was recovering. In spite of a devastating loss, Robert’s ability to see humor in his own misfortune was greater than any inclination to feel sorry for himself. “Well,” he said, “At least that can’t say I’m talking out of both sides of my mouth any more!” Robert told me that if he had won the election, he probably would be dead because he probably would not have given the neuroma the attention it required.

Once someone wanted his picture taken between Rufus Edminsten and Jim Graham. Edminsten was North Carolina Attorney General from 1975 to 1985. Graham was North Carolina Secretary of Agriculture from 1964 to 2000. Both men were over six-feet-tall, quite a contrast to Robert’s 5 feet 6 inch stature. “How’s it feel to be photographed between two tall men like us,” Rufus asked him. Seemingly without thinking about it, Robert replied that it was “Like the dime between two nickels.” He was quick.

A voice of calm reason, he saved me a lot of trouble once. Another lawyer had stirred up a great deal of anger in me. I had written a letter to that lawyer and thought it was a masterpiece. Before I sent it, I showed it to Robert. “That’s a good letter,” he told me. “Now put it on your desk and don’t do anything with it for two weeks. I expect you will probably pick it up, read it, and drop it in the trashcan.” He was right.

He loved music and to dance. He met his wife, Katie Earle Owen, on the dance floor at ECTC, during his first two years there. Years later, they ran into one another, chatted, talked about dancing, and began dancing again.

“My doctor asked me the secret of how I stayed so healthy,” Katie told me this June. “I told him ‘Dancing! I love dancing! And the faster, the better!’” She and Robert lit up the floor with their jitterbugging whenever the Lillington Rotary Club held its annual Cornelius Harnett Ball.

So what was it that led a poor farmer’s son from Harnett County, North Carolina into the halls of power?

It was his mother and father who loved him and sacrificed for him, setting the example of “service to others.”

It was devotion to his loving wife, Katie, and their children, Margaret, Mary and Rupert, and his grandchildren, Emma, Heather, Elizabeth, Grace, and Robert.

It was his quiet and sustaining faith in God and Christ, having been a member the Baptist Church, beginning at Neill’s Creek Baptist Church and at Memorial Baptist Church since its formation.

It was a very special love of life made complete by an overwhelming sense of thankfulness for all the good fortune that had visited him throughout his life.

It as all that. And more. He was my friend. And I miss him.

Robert, Mary and their grandchildren

Robert and Mary with Children Mary, Rupert and Margaret.

Sunset and evening star,

And one clear call for me!

And may there be no moaning of the bar,

When I put out to sea,

But such a tide as moving seems asleep,

Too full for sound and foam,

When that which drew from out the boundless deep

Turns again home.

Twilight and evening bell,

And after that the dark!

And may there be no sadness of farewell,

When I embark;

For tho' from out our bourne of Time and Place

The flood may bear me far,

I hope to see my Pilot face to face

When I have crost the bar.

– "Crossing the Bar"

Alfred Lord Tennyson (1889)

Robert once told me that when he was running for Clerk of Superior Court, he would drive to Harnett County every weekend to campaign.

“‘Knock on every door you can,’ they told me, ‘Stick your hand out and say, Hello, I’m Robert Morgan.’”

He finished by saying “But, Jim, I’ll tell you: every time I knocked on a door, I was praying, ‘Please, don’t be home! Please, don’t be home!’”

He got over that. And I am certain that on the morning of July 16, this year, the old sailor crossed the bar. I am also sure that as he approached The Pearly Gates, he looked Saint Peter right in the eye, held out his hand and in all earnestness said, “Hello, I’m Robert Morgan.”