The Rearview: Carolina's Vintage Cars

/Introduction by Brittney Forrister Photographs by Ronny Nause

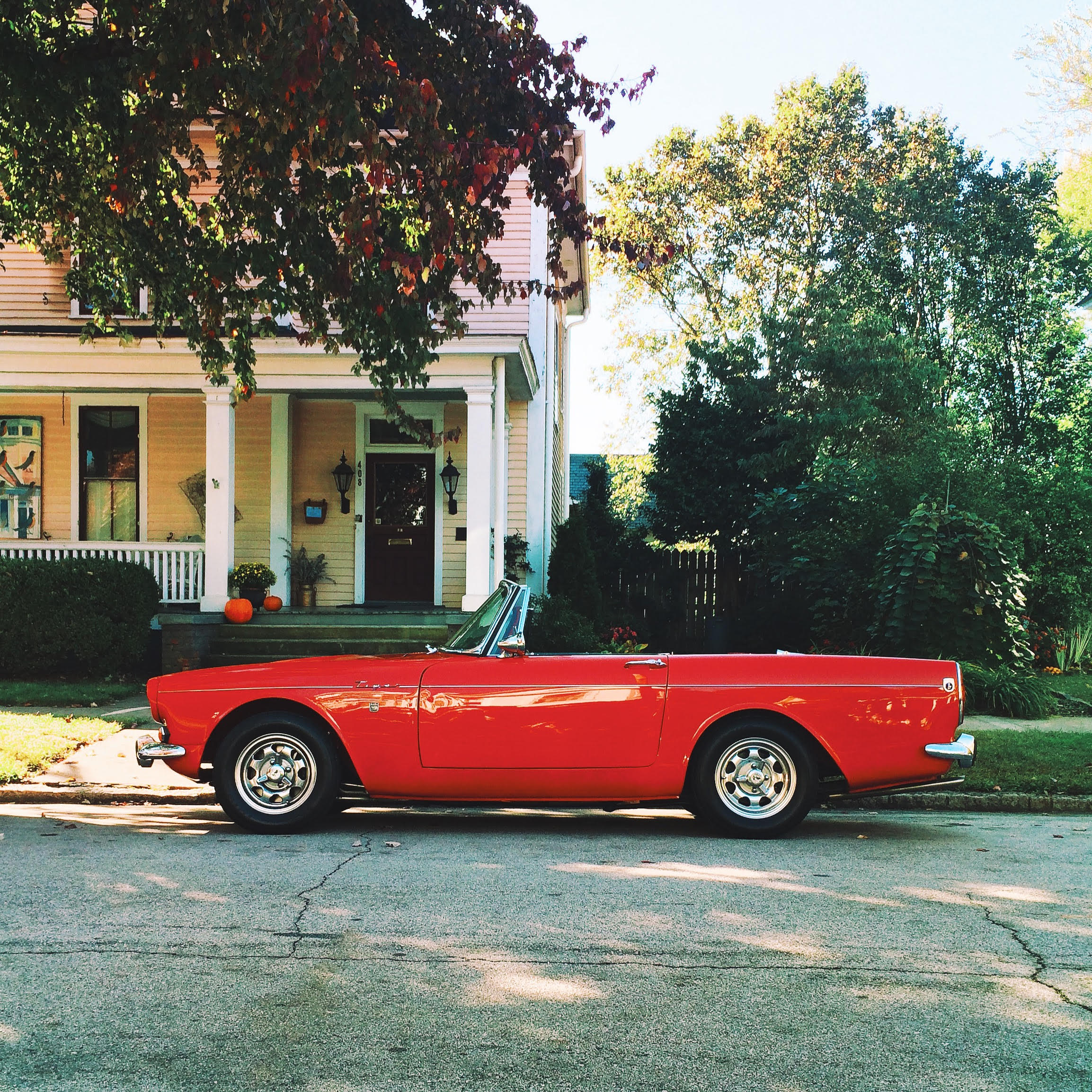

Cars are important here. From racing and rehabbing to the Sunday afternoon drive, they aren’t just practical. They’re recreational. We hold our breath and plug our ears at the Charlotte Motor Speedway and on bleachers beside old dirt tracks in forgotten towns. We self-soothe and cruise with no particular place to go along secluded backroads, mountain curves and national seashore highways. We marvel at the bright colors and sleek lines of vintage cars that seem to be at every local fair and on every city block across the state. Cars are a way of life.

Photographer Ronny Nause knows this. He’s been documenting whips for years. This week he takes you on a tour of the Triangle’s best rides, as Brittney Forrister, the daughter of a car enthusiast and salesman, explores what cars mean to her.

Hop in and let's go for a ride.

I grew up on a car lot in the most western part of North Carolina. Dad opened the lot on a large hill beside our home overlooking Highway 64 when I was five, and by age nine I was helping him park cars at dusk, positioning each according to the next, so if you squinted at the row of bumpers, you saw one collective gleam of chrome. I’d walk car to car with a bottle of Windex and a few pieces of newspaper, rubbing the windows clean and making sure all the tires were turned at the same angle. There is nothing more familiar to me than the smell of rubber and grease and the sound of keys jangling, coke cans shifting in a vending machine, and my dad singing Waylon’s Waymore Blues at the end of a buy-here, pay-here day.

Before cars paid the bills, cars were a passion. In a former life, Dad sold insurance 9-to-5 and took the inside curve every Saturday night at Tri-County Raceway, a local dirt track seven miles outside of Murphy, NC. My mother, pregnant with me at the time, cheered him on from dirt-caked stands. It wasn’t just the speed, though. He has always loved the design and engineering of a polished machine, and he taught me to appreciate a car’s proportion, its curves, the details of the dash, the smooth grain of wood paneling and the whimsical pop of a hidden headlight. To him, a vehicle is architecture in motion, a powered piece of art.

On nights we’d finish up early at the car lot, and something new had been added to the inventory, he’d look at me with excitement and say, “Let’s take her for a drive.” The valley echoes of the Appalachian Mountains would soften the hard edge of the motor as we slid through the curves of Sunny Point Road, hugging the yellow line as we turned left, negotiating the white line as we turned right. When we approached a straightaway, Dad would use a heavy throttle, throwing us back into our seats, passing through the shadows of the treeline, and I would giggle. It wasn’t the act of driving, it was the art of driving, and I was taught at an early age the high and the low, the fast and the slow of cruising. I was schooled in automotive cool; clean car, black tires, and a sweet sound. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I’m sure those drives were my father’s way of connecting back to his passion, not just a bill of sale. He was reliving his past; when cars were a dream to be had, a privilege for few, a rite of passage, a sense of freedom, and above all, a thrill.

When I reached the age of freedom, gas station lattes, young love and away games, I was behind the wheel and toeing the county line with nowhere to go. And nowhere I went. With less than a mile of strip, four lanes and a stop light, Murphy was a cruising town. On any given Friday and Saturday night, most teenagers, including myself, would slowly roll down Peachtree Street and circle back to repeat. Windows down, Semisonic up, we took the school halls to the streets, leaving a trail of winks, whispers, and the scent of Bath & Body Works Sun-Ripened Raspberry wafting through the open, tinted windows. We worked our way from Point A back to Point A, nowhere to go but there, sweating the clutch to accelerator ratio on the steep part of Laundry Hill. It was a drive-by and wave culture, innocent as any teenage amusement could be, and sometimes, Dad would let me take one of the garaged cars. My favorite was the 1979 triple black VW Super Beetle Convertible, one of the rarest and most sought-after drop tops of that era. It has since been sold, but I still see it around town and think about those nights we stargazed at 15 miles per hour.

Car culture shifted in Murphy. People got home computers and usernames. Downtown businesses, and new-to-town retirees who complained about the traffic made my generation among the last of the cruisers. I graduated high school and took I-40 East in a car that made sense for the long-haul. In the years following I went from Point A to Point B in any mode of sensible transportation available. A few years ago, however, I found myself in a job I didn’t love with a few extra dollars in my pocket. I was spinning my wheels, going nowhere. I called Dad for advice. His solution: One of his famous mixed CDs, entitled “The Rearview,” and a 1981 CJ-5 Jeep Wrangler Renegade. I met him in the parking lot of PF Changs to pick her up and make my first payment. 1981 happens to be the year of my birth, and the next to last year of production for the CJ-5 model. Restored about 10 years before it was mine, the original soft yellow paint with two-tone orange stripes has a nice patina, and is equipped with an old “Bulletproof” 6-Cylinder engine, 4-speed transmission, and chrome Jeep Rally wheels.

Eventually, the jeep, along with some gumption, carried me in a new direction--a new job, a new house, a new pace. And, like my father, when the day’s work is done, I climb into the jeep and go for a drive. I think about my past. The dreams I had when I was 16 and the dreams I have now. I enjoy the freedom and privilege of escape. But mostly, I just drive for the thrill of it.

Nowadays, people are starting to look back as a way of moving forward. It’s said, “they don’t make them like they use to” and we’re a state that can appreciate the “use to.” Artisans, brewers, stylists and chefs have gone vintage and old cars are the new nod to the past. When you transpose that movement on a North Carolina road map, it highlights back roads with untold stories meant to be appreciated at a slow drift. In a state with a rich history of racing, a diverse terrain worthy of exploring, and a collective eye for the unique, many folks are embracing the act of cruising again; Younger generations are looking under the hood and kicking the tires, mixing and matching new parts with old frames. And like whitewashed denim, the newer models, the 80s and 90s, are still thrift garage affordable. If you’re interested in learning more, I know a guy. Head west and look for the car lot on the hill.