Needle & Ink: The Heathen Ways of Overeducated Tattoo Artists

/Story by Hannah Collier Photographs by Baxter Miller

Alex Carter points to my ears. I’ve got eight piercings total, which pales in comparison to the body modification work he has.

“You’ve got a couple earlobe piercings. That pretty much started from the ‘70s with Jim Ward opening the Gauntlet, which was the industry’s first piercing-only shop. Jim Ward is commonly referred to as the father of modern body piercing,” says Alex.

He continues, “Then on the other side of it, you’ve got Fakir who started the modern primitive movement about the same time, which is where you see people like me who have the larger gauge piercings. This has been around for centuries. It’s been around almost as long as man has. Tattoos, larger piercings, stretching piercings. But, Jim Ward and Fakir both moved it into the 20th century as far as the materials, the techniques the aftercare, things like that.”

Alex is at the center of the modern body modification movement in Raleigh. He’s worked the front desk at Warlock's Tattoo shop for 10 years, although the title “Front Desk Manager” sounds too corporate to describe what he does. Gatekeeper is a more accurate description. While he doesn’t actually tattoo or pierce, Alex is the go-between clients and the tattoo artists.

The phone rings and mid-sentence Alex swears, pauses, and switches gears to talk to a customer.

“Warlock’s Tattoo?”

He states the shop name in the form of a question. I can hear the customer on the other line ask about getting a piercing.

“Typically anything with titanium is going to start at $50, and anything set in gold is going to start at $80, and we go up from there. It’s a walk-in only service, and we take walk-ins every day from noon until an hour before our posted closing times. Today we’ll be here till 10 o’clock for walk-ins. No problem. Bye-bye.”

Most of the afternoon goes like this — I ask Alex questions as I’m hunkered down behind the front desk that he answers between fielding phone calls and walk-in client questions. With a distinct candor he relays tattoo and body modification history lessons colored by his own personal anecdotes. Most of the shop’s nine artists are busy with clients, so Alex introduces me to them by pointing to their workspaces.

“You’ve got Julio. He’s from Guatemala, his mom moved him and his siblings when he was four or five to California. He grew up in LA, moved out here, apprenticed here eight years ago, and now he’s just stayed with us... You’ve got MJ, he’s another artist who went to Carolina. Played football for them, got his degree in art and communications. Self-taught tattoo artist. It’s really hard to do, you don’t see much of that these days.”

Alex continues. “Ernie, he’s been tattooing as long as Byron [the shop owner] has. I don’t know what he was doing before that. Mike used to be a survey engineer, construction and landscaping. Kevin, I don’t know what he did before he started tattooing.” Kevin later told me that he had been working in Washington D.C. in a government job, then went back to his Alma mater JMU to get a degree in fine arts before he started tattooing. “Rich... he was in the Marine Corps in the ‘80s, he also went to school [at Tulane] and was an architect for a while.”

Some of them stop by the desk to offer commentary on my presence. At one point, Mark, the resident piercer at Warlock's and Alex’s best friend and roommate, walks by and quips, “What the hell are you doing behind my desk?” Later Kevin asks of my interview, “It’s a social anthropology on the heathen ways of overeducated tattoo artists?”

MJ, A UNC ALUM AND FOOTBALL PLAYER WHO OPERATES UNDER THE MONIKER, "SKUNK MONKEY," TATTOOS ADAM BIGGS WITH THEIR COLLABORATIVE INTERPRETATION OF ARMOR

Rich tattoos in his workspace with his Tulane diploma hanging above

Mike tattoos an homage to his client's native american roots, a wolf with feathers

The connection between tattoos and “heathen ways,” is part of what I am trying to uncover in my conversation with Alex.

“In a lot of ways the popularization of this industry has been a double-edged sword. It’s becoming way more acceptable, which is awesome. Tattoos, piercings, body modification in general isn’t just for the scumbags of the earth like most of us,” says Alex referring to the shop employees.

I laugh and say that we’ve all got a little bit of scumbag in us. Alex has other ideas.

“Eh, some more than most. We’ve got people from all walks of life coming in here. It’s awesome. It’s getting more acceptance in the workplace — Petsmart, Starbucks, several of the bigger chain companies are starting to get a little bit more lax about tattoo policies. The military is getting a little bit more lax. The Navy now allows hand tattoos and you get up to one square inch area on the neck. Cool. But then you [still] get people who — they’re pretty much letting it be the full representation of their personality. ‘Oh, I’m tatted. Oh I’m pierced.’ You know, people like that ‘Oh you know I want whatever’s gonna get the chicks.’”

Alex’s respect for the industry began in his childhood. He grew up around motorcycle clubs with a military father. He is sitting at around 150 hours of work in a tattoo chair, with the most recent piece being a set of ravens in progress on his ribs that reference the god Odin in Norse Mythology. He also has plans to cover both of his arm sleeves that currently display images of skulls and fire. On one arm he wants to tackle a newer method of blacking out the entire arm, and then having an artist do white-ink detailing over top of it. For the other arm he has plans to do a biomechanical sleeve, and use the heavy line work to cover the existing images.

These tattoo projects are only one aspect of his body modifications. Right away I notice his gauged ears and lip plate. What I don’t notice is that he has a split tongue. He points it out to me, explaining that the tongue is already two separate muscles encased in one membrane, and all tongue splitting does is separate the membrane. He talks about an emerging movement called biohacking — “More or less hacking into the body’s physiological responses, and the mechanics of the body to change something or take advantage of it” — then proceeds to show me how the small silicone coated magnet embedded in his fingertip can pick up objects like a paperclip. He likens the sensation to a 6th sense of sorts, or to licking 9-volt battery — which apparently I’m one of the only people he’s met who hasn’t tried.

“I first saw them the way most people did, you know, six, eight-years-old sitting in a dentist’s office. You look at the coffee table there’s a National Geographic sitting there, and you’re flipping through it like ‘that looks so cool!’ And as I got older I joined the military, so it’s not something I could do. It kind of just went to the back burner. When I got out it turned personal, political… I kind of jumped headfirst into it because after six years in the military I got out on a ‘fuck this country level.’ It became a push — which I guess is where my personality comes into it — a push to not really, I guess represent the society I spent six years doing whatever for. I more or less pushed myself to the outside, [and] you know, [brought] what I feel inside to the surface. Visibly make myself different from a lot of the other people I could commonly be associated with... that I used to be associated with.”

Alex displays his newest piece of artwork, a set of ravens that reference the god Odin in Norse Mythology

“Good afternoon, this is Warlock's… Corner of Western and Jones Franklin road, it’s the Plaza West shopping center with the Harris Teeter and the Sonic… We’ve been here 26 years man, we’re not going anywhere.”

The Harris Teeter played a very important role the first time I visited Warlock's. After forgetting to eat breakfast and nearly passing out during my measly 15-minute session in the chair, one of the shop artists, Julio, ran over and grabbed me a soda and candy bar to get my blood sugar up. I’m not the only one to nearly pass out in his chair. Warlock's has seen a number of incidents like mine over its 26 year history, which is why they emphasize safety and care.

“A lot of people jump into this stuff not realizing a lot of the social and physical ramifications of getting it done. You know tattoos still have a lot of negative stigma associated regardless. We pretty much stress to kids that come in here, kids 18, 19, 20-years-old, ‘Get where you want to get first. And then put yourself in a position where they can’t fire you, they can’t look down on you, then push the envelope.’”

After wrapping up a tattoo session, the shop owner Byron Wallace joins Alex and me at the main desk. He shares Alex’s mindset on educating younger clients, recalling the story of his first tattoo, which had absolutely no meaning.

“I was 16 and I lied to the tattoo artist and promptly went home and got my ass beat by my dad,” says Byron. “It was a little cheesy rose with a skull. I was just infatuated and scared to death when I went into the tattoo shop. Which is a lot like a lot of our clients who come in here and they’ve never had a tattoo.”

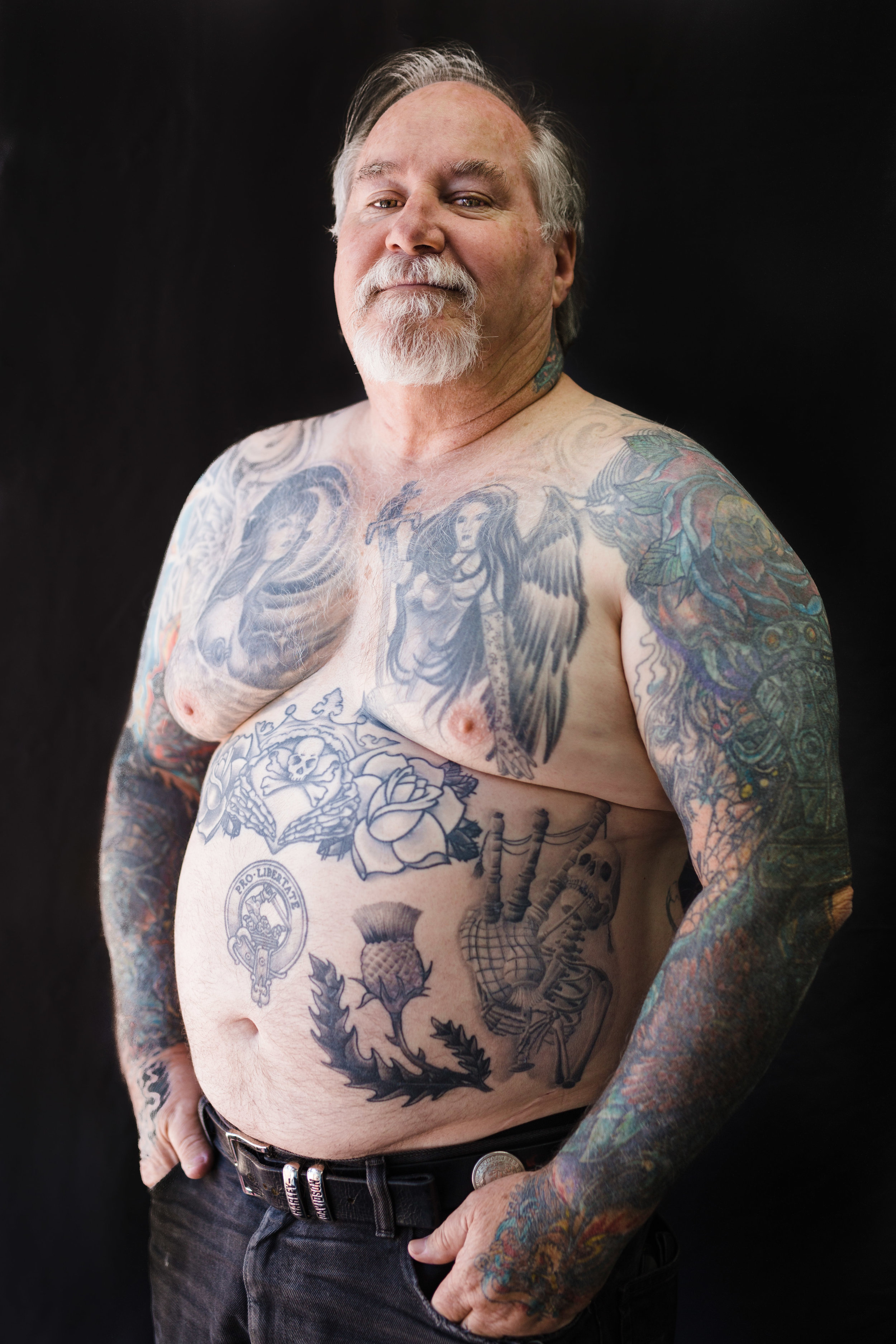

Shop-owner, Byron (left) and "gatekeeper"," Alex

Throughout the course of the afternoon, I watch both Alex and Byron patiently explain the nuances of tattoos to several first time clients. It’s like the parents saying “don’t do that,” but with a perfectly logical explanation every time as to why. They’ve clearly had this conversation hundreds of times.

Their advice includes: Don’t get a tattoo on your fingers. You can, but it will only be semi-permanent and fade. Don’t get that elephant tattoo on your stomach if you ever plan on having children. You can, but that cute little design will just stretch and blow up. Don’t get tattoos of names, it’s the “kiss of death.”

Before Byron opens up about his entry into the world of tattoos, he makes sure to inform me that I’m sitting in his desk chair. I can’t tell if I should laugh or be apologetic, and after awkwardly offering the chair back to him, he declines and leans up against the outside of the desk.

For the first time all afternoon I am acutely aware of the constant sound of tattoo machines buzzing in the background. If you’ve never been inside a tattoo shop, imagine a dozen electric toothbrushes playing white noise in the background. Byron is much more calculated with his words than Alex. He is hard to pinpoint. Wise and intimidating, but kind and comforting at the same time. He teases me about being a Yankee, and I pull my corniest “But I’m not a Yankee, I’m a Red Sox Fan!” joke on him to which he responds a stoic stare. I laugh it off, embarrassed, trying to justify that my dad is from North Carolina. He rephrases, “If you’re from Rhode Island and you moved down here, actually you’re a damn Yankee.”

Though he’s firmly settled south of the Mason-Dixon Line, Byron has lived many places. Originally from Southern California, he spent most of his childhood living between Puerto Rico, Cuba and Japan as the son of a Navy father. He later moved to Texas, and then Oklahoma City for a tattoo apprenticeship under Johnny Dragun after a motorcycle accident forced him to switch careers from auto mechanics to something less labor intensive. From there he moved to Raleigh to join his brother. The two opened Warlock's in 1990, and his brother has since moved north. Byron tells me that he and his brother are the oldest set of twins that tattoo in the United States.

In fact, all three of the Wallace brothers are professional tattoo artists, a detail that Byron ironically claims as “justice” for his father’s disapproval of that first tattoo.

I try and dig to find which of Byron’s tattoos are the most meaningful or storied. He and Alex both assert that some tattoos just aren’t meaningful. They are artwork done for the beauty of the art itself, or in some cases on a dare. Byron tells me that he doesn’t have any stories for his favorite tattoos, but still reveals bits and pieces of their meanings throughout the afternoon.

“I have in memory a piece for my dad that’s a Navy tattoo. And then I’ve got a little slice of cake for the artist that we ended up losing here that ended up committing suicide. I’ve got a memory piece for him, but a lot of the artwork that I’ve got is just stuff that I really, really like. It deals with Day of the Dead. I like the cultural meaning about Day of the Dead. They celebrate life, and they don’t forget about their loved ones after they die.”

Day of the Dead imagery appears throughout the shop. The walls are covered in reference material for clients to look at for tattoo ideas, as well as artwork that Byron has collected over the years. He points out some of his favorite pieces to me, including a large portrait of a woman in Day of the Dead attire that hangs between the tattoo section and the piercing section of the shop. Byron has a deep understanding of the human body, of how to deal with death and how to deal with pain, which is completely practical knowledge for a tattoo artist.

“My first two tattoos I ever did were on myself. That way my teacher knew I knew exactly how humble to be when you stick somebody.”

The phone rings again and Alex answers it in the background while Byron talks to a first time client looking to get a price estimate on a tattoo.

To my left, Alex is saying, “Ernie Red? No, we have an Ernie Rose.”

On my right, Byron is laughing when the customer gets excited. His estimate is less than she was expecting. “You can shop around for a tattoo like you can shop for anything else. The thing is, we’ve been here for 26 years, and we don’t try and sit here and kill our clients.”

They finish their conversations at almost exactly the same time, with the same parting lines. “Yeah it’s no problem at all man.” Alex hangs up the phone just as Byron is waving to the woman as she walks out the door. He says, “No problem!”

Alex had just gotten a call from a tattoo artist in Melbourne, Florida, who found a tattoo machine at a pawn shop that said “Merry Christmas Ernie” on its frame. He had been calling around to any shop with artists named Ernie to try to track down the story behind the machine. The machine didn’t belong to Warlock’s Ernie, but it prompted Byron’s memory.

“I was supposed to get a machine when my teacher [Dragun] died, and it used to belong to Lyle Tuttle. It’s called the Frisco flyer, and there was only a handful of them made. I’ve actually got it tattooed on my ankle.”

Byron points to his ankle and continues. There had been an issue with the handling of the will by Dragun’s estranged daughter, and Byron was contacted by the woman in charge of the estate sale because of his connections to Dragun. He got himself into a bidding war for the machine with another buyer, who turned out to be Lyle Tuttle himself. Byron and Lyle are old friends, and they made a deal so they could both get the machines they wanted from the estate.

“So I flew out there to go pick up this machine to make sure that nobody else got it. I stop by [Johnny’s house], introduce myself to the estate lady and go, ‘I’m here to pick up the Frisco Flyer,’ and paid her $1,700 for it. She could tell that I was really, really ecstatic about it. She goes ‘What’s the machine worth?’ I go, ‘You really want to know? You tell Johnny’s daughter I would’ve gave her fucking 10-grand to get that fucking machine from her. I would have gave her anything. That ties Johnny, Lyle Tuttle, and myself all together, because all three of us know each other. I’ve known Johnny as long as I’ve known Lyle which is about 40 years… It’s the story behind it.”

Only Byron, Lyle and Johnny know the depth of the story behind that machine. It’s one of many examples I hear about the comradery of the tattoo community from Byron. The proceeds from most of the original artwork on the walls at Warlock's went to a hardship fund for artists who are down on their luck. The National Tattoo Association that Byron and Warlock's belong to maintains a scholarship fund for children of tattoo artists to help with college tuition. This September Warlock's is partnering with the Ray Price BikeFest Motor Expo for the 6th time in downtown Raleigh and donating half of the proceeds to the USO and the United States Veteran Corps of America.

A customer looking at reference art chimes in when we bring up tattoo conventions. He had come to Raleigh from Goldsboro about six years prior for a different tattoo convention, but the facilitator had taken off with the money. Instead, he brought his business to Warlock’s. “You worked out good for us. We came in here and had a good time, good tattoo.”

Byron remembered that convention, the man ended up getting indicted on federal charges for stealing the money. “That’s one of the reasons why we went back with Ray Price, and started the festival down there at BikeFest.” Byron's respect for and connection with the tattoo community is the kind that keeps clients coming back six years later.

I comment to Byron that it seems like a very big community infrastructure. He laughs.

“It’s more like a family infrastructure.”