Farmworkers in North Carolina's Local Food Movement

/Story by Sandra Davidson Photographs by Baxter Miller

Ramon Zepeda is Mexican, and he is American.

He speaks Spanish, and he speaks English. He has worked on a farm, and he advocates for farmworkers. He is rural, and he is urban. Ramon’s philosophy of the farmworker struggle, though common among many first-generation migrant youths, acquires special meaning when placed within the new Southern food movement.

High-end Southern food, created by master chefs, relies on locally farmed food and produce. Migrant farmworkers are the backbone of this recently booming industry. Andrea Reusing is the owner and head chef at Lantern, a renowned farm-to-table restaurant situated on Chapel Hill’s legendary Franklin Street. Andrea is deeply aware of the role farmworkers and undocumented laborers play in the food system, but like many advocates is frustrated by the invisibility of the issue. “If you’ve ever eaten chicken in the United States you’ve benefited from an undocumented worker. If you’ve ever eaten food off a clean plate in a restaurant, you’ve had this benefit,” Andrea says. “I am reminded daily of the sacrifices people make to work and live in this country.”

Ramon and his family have made such sacrifices.

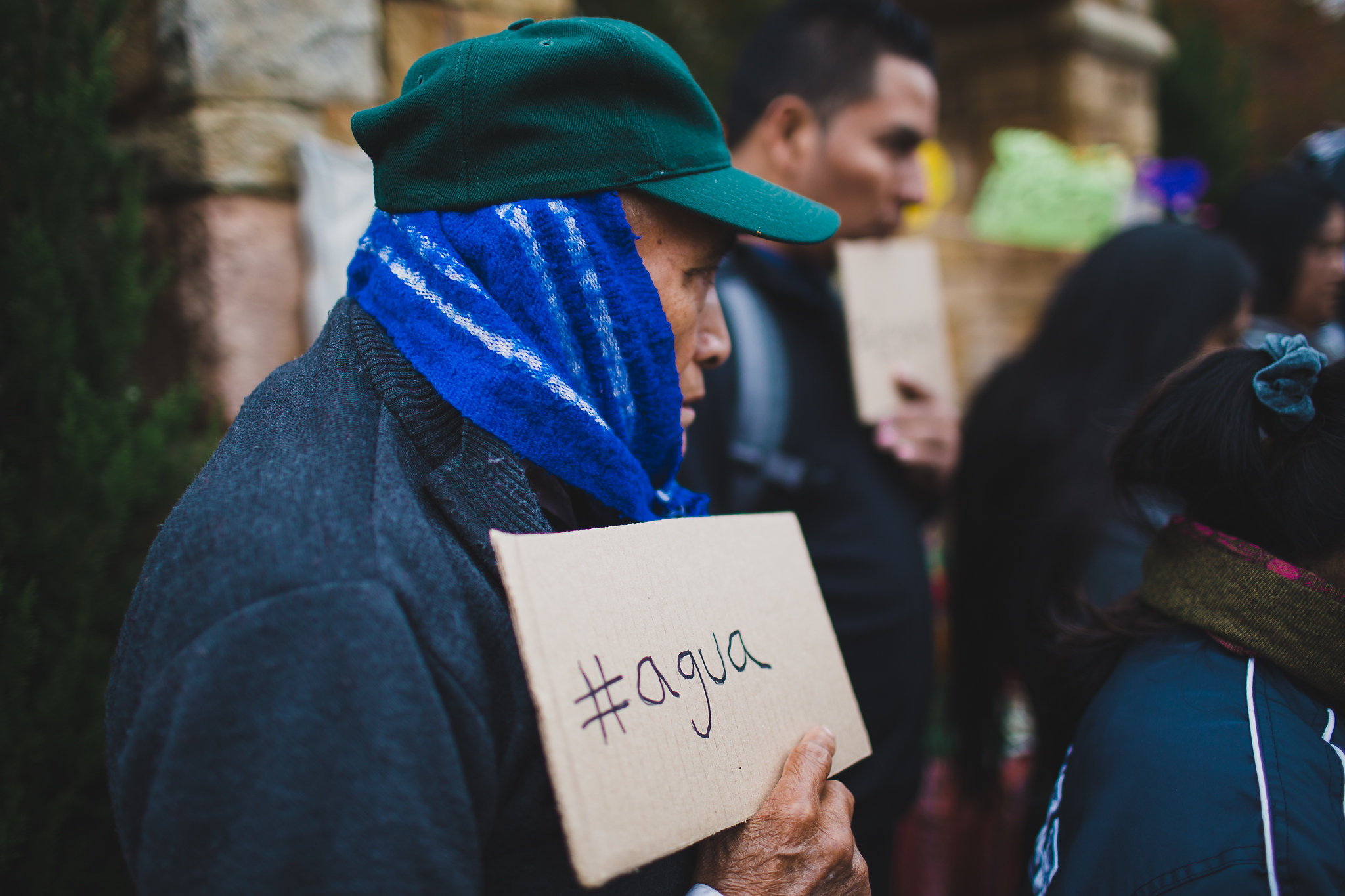

On a cold, drizzling Saturday last October at the historic Oakwood Cemetery in downtown Raleigh, Ramon was at an Día de Los Muertos press event organized by the North Carolina Farmworker Advocacy Network (FAN). He was translating stories of strife from Spanish to English. Immigrant field and factory workers were there to raise awareness about inhumane working conditions in North Carolina and challenge policymakers to pass stronger laws regulating working conditions and enforce the ones already on the books.

The field and factory workers spoke powerfully. Some workers showed their crooked fingers and spines, deformed by repetitive, labor-intensive factory work. Others read obituaries of fellow workers who died from unsafe working conditions. One recognized an unnamed worker who was crushed beneath the wheels of a school bus. The worker had sought refuge underneath the bus, the singular source of shade on a particularly hot day of fieldwork, and was dozing when it drove off. It was a compelling event, and Ramon effectively translated the words and emotions of each worker’s story to a small audience of press, fellow advocates and curious visitors.

Ramon is often translating, both literally and figuratively. As the program director for Student Action with Farmworkers (SAF), an independent nonprofit with an office at Duke University's Center for Documentary Studies, it is part of his job to bring the marginalized stories of migrant labor struggles to broader audiences. He is constantly making sense of what it means to have a foot in the world of labor struggle and advocacy. This struggle is deeply personal to Ramon. He hails from Mexico, and has worked as a farmworker. He has family who still does.

Juggling these roles is difficult. “Sometimes I still feel torn between two worlds: being an advocate and being just who I am with my family," says Ramon. "I feel like I’m from Mexico, but I’m here in the U.S. or when I have to transition from English to Spanish. It’s just one of those things. I have to live in two worlds.”

Ramon’s journey to advocacy is deeply tied to trade and economic and social policies that have shaped agricultural practices in the South and beyond. Ramon was born in 1986. He spent his first decade in Santa Isabel de Quililla, a small town in the state of Jalisco, a region along the western coast of Mexico, several hours south of the U.S. border. Mountains surround the arid, dusty landscape. Ramon remembers, “It was like a bowl, like I lived in a bowl. I used to think what if people can look into this bowl?”

Ramon’s paternal grandfather and his brothers were one of the first families to own land in that area when it transitioned from a hacienda after the Mexican Revolution. The fourth of eight children, Ramon helped his family farm corn and beans and tend to cattle. “Any of us who were old enough to go out and work in the fields [helped],” he recalls. Outside growing season Ramon attended school and spent time playing outdoors, while his father temporarily migrated to the U.S. for seasonal farm work. “I just remember nature. Swimming in the rivers, just going out. That was our way of playing and having fun.”

Ramon estimates that 100 to 200 residents, mostly farmers, lived in Santa Isabel de Quililla during his childhood. It is even smaller today. Making a living farming corn became nearly impossible after the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), when the United States began to sell corn to Mexico more cheaply than it could be raised. Many families in town migrated to the states for better work, including Ramon’s. Today, some of those who have stayed grow agave to make tequila.

“Every year we had to borrow money from the bank to get fertilizer,” he recalls. “My family had to go in debt every year to get fertilizer to grow our crop to get us food to eat.” This became unsustainable and in 1994, when Ramon was 8, his mother and younger sisters joined his father in Los Angeles seeking opportunities. Ramon and his older brother Junior lived with an aunt and grandparents in Mexico for three years after his parents emmigrated. They were the last of his siblings to move to the U.S., joining their parents in 1997.

"I remember daydreaming about what it would be like when I arrived there. I remember dreaming about a border and a desert, but I couldn’t see further than that," says Ramon. "Somehow that was the image that I had—a big fence.”

It took Ramon a week and a half to travel the more than 1,500 miles to formally cross the border into the United States via Ciudad Juarez. At the time of his migration, his mother worked as a seamstress, and his father worked at a meat-packing plant. After several years in the United States, his father had obtained permanent resident status and legal documents for all of his children.

Leaving Mexico so quickly was difficult. Ramon remembers, “It felt super fast ... I don’t think I ever really got to process [it]... I don’t think I’m even there yet. I do think I was pulled too fast and put somewhere else.”

Ramon enrolled in Eastman Elementary school in east Los Angeles a week after he arrived in California. He spent the days leading up to school begging his mother to give him one more week to try to learn English. Eastman was jarring. He was placed in a bilingual classroom, but the size of the school and language gap was overwhelming. He worked hard in the classroom, and strove to learn English, but moving from a small rural town to a big city was difficult.

Ramon’s family rented a two-bedroom house in a rough neighborhood. Ramon walked to and from school every weekday. Fearing gang violence, Ramon’s parents prohibited him from leaving the gate of their house when he was not at school or work. Behind the gate he would play fetch with the family dog and practice soccer.

“When I was back home, in my hometown in Mexico, I could go miles and miles away, go to the mountains and do whatever. It was free. My parents were not worried that I would get shot.”

“Those years I was trying to find my place, find myself," says Ramon. "I was trying to be a kid and teenager at the same time.” Money was tight, and he quickly got a job at a car shop. Ramon and his siblings collected and recycled cardboard boxes and cans from their uncle’s restaurant and taco stand for extra money. “My parents were always working hard. We were a big family, so we were always trying to make ends meet.“

The plan was never to permanently relocate to the United States. “We didn’t see ourselves establishing in the U.S.,” he says. “We saw ourselves back in Mexico living in our hometown again, eventually.”

Life in California became difficult after the meat-packing plant where his father worked closed, and in 2003, Ramon and his family moved to Raeford, NC, again seeking better opportunities. At the time, his maternal aunt and uncle were running Taqueria Jalisco, a Mexican restaurant in Raeford. Ramon first visited them in earlier that year on a trip with his mother, and remembers thinking, “My dad’s going to like this. It looks a lot like Mexico because it’s open and has a lot of trees.”

Tobacco and cotton fields cover much of Raeford’s landscape. It is an agricultural community. At the time of Ramon’s move, the community also had a chicken and turkey processing plant. The 2000 census counted 3,778 residents in Raeford, a stark contrast to the 3.5 million in Los Angeles. The biggest cultural event in Raeford was the annual North Carolina Turkey Festival.

Relocating to North Carolina was another culture shock. The family moved in early fall. His father began working a small farm, his mother worked at a restaurant, and sometimes joined his younger siblings who began working one of several seasons of "topping the flower" of tobacco. Ramon started at Hoke County High School, where he first grappled with race. One afternoon he witnessed a fight at school. As it settled, Ramon says many of his classmates sorted into groups of “Mexicans, Native Americans, Blacks, Whites.” He’d never seen peers self-segregate along racial lines. The moment was a reality check.

Ramon was an active high school student. He played soccer and got involved in leadership clubs through the Hoke County Migrant Education Program (MEP), a federal education program designed to help migrant children achieve academic success. It is through this club that he first encountered Duke’s SAF. Through SAF and MEP, he attended youth leadership conferences and founded AIM: Action, Inspiration, Motivation, a student group that helps migrant children finish high school and go to college.

Many farmworker youth drop out of high school, and SAF and the MEP focus on education as a path to better opportunities. The programs did not let Ramon slip through the cracks. Many of his classmates did not graduate, and Ramon did consider leaving high school to pursue full-time work to help support his family, but SAF and MEP staff encouraged him not to do this, and with their help he graduated high school and enrolled at UNC-Pembroke.

During college he remained connected to SAF, and after his freshman year, he participated in an summer internship with them working for a Western North Carolina Workers Center and a supporting union trying to organize a poultry plant. It was there that Ramon was exposed to a different side of laborers’ struggles. He had worked as a farmworker in Mexico and was familiar with his father’s experience working in factories, but during his internship he learned to question the working conditions people deal with to make a living. He met with workers who damaged and maimed their hands pulling chicken bones apart as they tried to keep up with the speed of an assembly line, and others who were not able to take bathroom breaks on the job. The stories he heard that summer from laborers compelled him to consider what he’d accepted as a way of life for years. Ramon explains,“I feel good at the end of the week when I get my paycheck. Everybody does. But what happens in between? It’s always about the money, but what about the treatment or the working conditions?”

The summer internship prepared him to work as an advocate. After graduating from college, Ramon went to work for the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) as a labor organizer. He helped organize meat-packing, poultry and grocery store workers across the country.

Ramon has spoken with many laborers throughout the U.S. and has noticed patterns across the country at meatpacking and poultry plants. “There was a sense that you have to do the work fast. It’s dangerous, but you just have to do it.” He believes many laborers still hope for the American dream, but exploitative labor practices keep it out of reach. “The people in power, the employers, can hire people to undermine organizing efforts and unions…A lot of times in campaigns when workers were talking about, ‘Let’s organize and build a collective voice to address our working conditions,’ a lot of times it turned into, ‘Well this group isn’t working hard enough, or this group is stealing.’ It was damaging," says Ramon. "I’ve seen good people come together and try to change things and build power, but they are replaced or they are made an example of to discourage other people from organizing.”

In 2011 after three years as a labor organizer, Ramon went to work with SAF in Durham where he now lives with his wife and baby. He turned 30 this year and has lived almost twice as long in the U.S. as he did in Mexico. He is passionate about his job, but can feel disconnected from the farmworker experience. He explains, “I easily forget sitting behind this desk. I get into doing what I do. It’s good work but it’s not the same to sit behind a computer than to actually live and be taken back to the fields, to the conditions.”

Ramon often visits his parents to reconnect to his roots and the farmworker struggle. His parents still live in Raeford, and plan to be there indefinitely. The space and land available to them in North Carolina has deeply affected their quality of life. Ramon says, “When they aren’t working, my dad is out as if he’s back at home on his rancho. He has goats, chickens. He works and grows his garden every year. I think for him that’s his home. He’s been able to bring his home to Raeford. I think that’s what he was missing in LA. He didn’t have that. He was working in a plant. He was near cows and cattle, but it was not the way he wanted.”

Still, the longing to return to Mexico remains. His mother is grateful her children are in the United States with them, but she misses the family she left behind. “I think she misses being around her mom,” Ramon says. “In a way I also feel like my mom was detached from her family. I can kind of relate to my mom — feeling detached.”

Oakwood Cemetery is a little more than one mile from the heart of Raleigh, a growing city with a vibrant food scene. Urban gardens, and local brewers, coffee roasters and restaurateurs pepper the city. It feels progressive, exciting and youthful.

Durham, Chapel Hill, and Raleigh -- the three cities that make up North Carolina’s Research Triangle -- are the hotbed of the state’s burgeoning food movement. Local, organic, and seasonal -- food words with national currency -- characterize many of the farmers markets and menus in popular restaurants. Southern food, once lampooned and ridiculed for its unhealthiness and casserole crusaders, is having a moment. The rich culinary traditions in everyday food of the American South, with deep ties to African, Native American, Asian and Hispanic roots, are being celebrated in scholarly and popular media. The University of Mississippi’s Southern Foodways Alliance (SFA) is even using Southern food as a lens to explore, race and poverty, the region’s most challenging and deeply rooted issues.

At a Meredith College talk last year, John T. Edge, director of SFA, asked a panel of local chefs to speak to the most pressing issues in Southern food. Andrea Reusing, of Lantern Restaurant in Chapel Hill and 2011 James Beard award winner for Best Chef of the Southeast, discussed the success of bringing organic and local into popular conversation about foodways, and said the next logical step will be to talk about the conditions of the laborers.

Reusing believes human rights issues in the food system will eventually be impossible to ignore, but wonders, “How long does it take, and how many people are going to have to suffer in the process?”

Food injustices -- hunger, inadequate nutrition, child farm labor and dangerous factory work -- grow out of wealth inequality, a polarizing national topic. Reusing acknowledges the challenges of bringing the food laborer’s struggle to a broader audience, but says, “I think the foodie moment is now waking up and looking at how inequality really affects every part of the food system and visa versa."

Her comments echo Ramon’s position. He says the migrant laborers’ struggle should be framed as a human rights issue. “We don’t just say it’s the farmworkers because then we can easily say well, ‘They are foreign, they aren’t from here,’” he says. “If it’s all of us calling for [change], I think we will be more successful.”

Ramon and Andrea have never met, but both dream of a day when food products will have labels that indicate how and by whom they are harvested, and organizations like the Fair Food Program establish models for what this could look like. However, Andrea understands many consumers do not have the privilege of buying local food, but that any consumer can support organizations that advocate for food justice, like all of the coalition members of the Farmworker Advocacy Network which hosted El Día de los Muertos event last October.

She also advocates for consumers to have conversations with food workers across the industry. “I think the first step for a consumer is to try to talk to people,” she says. “Talk to people in grocery stores. Talk to people when you go to a farmers market. Really try to find out where this food is coming from.” Ramon too, believes the consumers must seek “socially responsible foods and services--not just local and organic.”